In many farming regions, including areas like Bangladesh where seasonal monsoons bring abundant rain but dry spells strain groundwater sources, livestock owners often face a critical challenge: providing consistent, clean drinking water without skyrocketing costs or risking animal health. Poor water quality—high in sulfates, nitrates, or bacteria—can lead to reduced feed intake, lower milk production, weight loss, digestive issues, and even serious conditions like nitrate poisoning or polioencephalomalacia in cattle. With animals consuming anywhere from 2–4 gallons per day for sheep and goats to 30–50+ gallons for mature beef or dairy cows, water isn’t just a necessity—it’s the most consumed nutrient and a major driver of farm profitability.

Rainwater and filtered water for livestock offer a powerful, sustainable solution. Rainwater harvesting captures free, naturally soft rainfall from barn or house roofs, while filtered water (often from wells treated with sediment, carbon, or UV systems) ensures reliability and contaminant removal. When managed properly, these sources deliver superior quality compared to untreated surface ponds or hard well water, cutting expenses, boosting animal performance, and enhancing farm resilience against drought or rising utility costs.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore the science-backed benefits, real risks, direct comparisons, step-by-step setup practices, species-specific advice, testing protocols, and proven strategies. Drawing from university extension services (such as Penn State, NDSU, and others), research on water quality, and practical farm experiences, this article aims to equip you with everything needed to implement or improve a rainwater and filtered water system for healthier livestock and a more sustainable operation.

Why Livestock Need High-Quality Drinking Water

Water is the single most important nutrient for livestock, influencing nearly every physiological process. It aids digestion, nutrient transport, thermoregulation, milk synthesis, and waste elimination. Dehydration or poor-quality intake quickly reduces performance: animals may drink less, eat less, gain weight slower, produce less milk, or become more susceptible to diseases.

Key water quality parameters include:

- pH: Ideally 6.0–8.5 (or 5.5–9.0 for most species). Too acidic (<5.5) risks acidosis; highly alkaline (>9.0) causes digestive upset, diarrhea, and reduced intake.

- Total Dissolved Solids (TDS): <1,000 ppm ideal for dairy cows; <3,000–5,000 ppm generally safe for most livestock, though higher levels cause reluctance to drink and performance drops.

- Sulfates: <500 ppm for young calves/sheep; <1,000 ppm for adult cattle. High sulfates lead to copper deficiency, polioencephalomalacia (a neurological disorder), reduced intake, and diarrhea.

- Nitrates: <100 ppm safe; 100–300 ppm caution (additive with feed nitrates); >300 ppm risks poisoning, reduced milk, abortions, or blue discoloration in mucous membranes.

- Microbial contaminants: Bacteria (e.g., E. coli, Salmonella), pathogens from runoff or stagnation.

- Other: Hardness (calcium/magnesium), iron, heavy metals—all can affect taste, intake, and health.

Poor water forces animals to seek alternatives (ponds, ditches), increasing parasite exposure, foot issues, or bacterial infections. In hot weather or lactation, intake doubles, amplifying problems. High-quality sources like properly managed rainwater or filtered well water prevent these issues, often improving weight gains by 10% or more and supporting optimal productivity.

Understanding Rainwater as a Livestock Water Source

Benefits of Rainwater for Livestock

Rainwater is naturally soft (low TDS, minimal sulfates/calcium/magnesium), making it excellent for species sensitive to mineral imbalances—such as goats prone to copper issues from hard water. It avoids many groundwater problems like high salinity or iron staining.

Key advantages:

- Cost savings: Free collection reduces reliance on pumped well water (energy costs) or municipal supplies. Farms can save significantly, especially in high-rainfall areas.

- Sustainability: Offsets groundwater depletion, reduces runoff pollution, and supports eco-friendly practices. In drought-prone periods, stored rainwater provides backup.

- Health perks: Cleaner than many surface sources; soft water improves palatability and intake. Studies show better performance when avoiding high-sulfate or nitrate wells.

- Reliability: Barn roofs offer large catchment areas; systems supply supplemental or primary water.

Potential Risks and Contaminants in Untreated Rainwater

Rainwater starts pure but picks up contaminants during collection:

- Roof runoff: Bird droppings, dust, pollen, leaves introduce bacteria, pathogens, or organic matter.

- Atmospheric pollutants: In industrial areas, possible trace chemicals (though generally low for rural farms).

- Roof materials: Avoid treated wood, asbestos, or lead; prefer galvanized metal or standing-seam roofs.

- Storage risks: Algae growth (if light-exposed), stagnation, mosquito breeding, or bacterial proliferation in warm conditions.

Poultry and young animals are more vulnerable to pathogens. Without treatment, risks rise—but simple practices like first-flush diversion and filtration mitigate most issues effectively.

The Role of Filtered Water in Livestock Systems

What “Filtered Water” Means for Farms

Filtered water typically starts from wells, boreholes, or surface sources and undergoes treatment:

- Sediment filtration: Removes particulates.

- Carbon filtration: Reduces odors, tastes, some chemicals.

- UV disinfection: Kills bacteria/pathogens without chemicals.

- Other: Reverse osmosis for high TDS (rare for livestock due to cost).

Benefits include consistent quality, pathogen control, and removal of heavy metals or excess minerals. It’s ideal where groundwater is reliable but needs polishing.

Drawbacks: Ongoing filter replacement, energy for pumping/UV, and potential residual chlorine taste (if municipal).

Rainwater vs. Filtered Water: A Direct Comparison

| Aspect | Rainwater (Harvested) | Filtered Well/Municipal Water |

|---|---|---|

| Cost | Low upfront; near-zero ongoing (free source) | Higher (pumping, filters, energy) |

| Availability | Seasonal; storage-dependent | Consistent year-round |

| Mineral Content | Naturally soft, low TDS/sulfates | Varies; often hard/high minerals |

| Treatment Needs | Filtration + first-flush essential | Filtration/UV often sufficient |

| Animal Health Impact | Excellent palatability; avoids deficiencies | Good if filtered; risks if untreated high TDS |

| Sustainability | High (reduces groundwater use) | Moderate (energy-intensive) |

Rainwater excels in soft-water needs and cost; filtered water wins for reliability. Many farms blend both for optimal results.

Best Practices for Collecting and Using Rainwater for Livestock

Designing an Effective Rainwater Harvesting System

- Catchment Area: Use clean metal roofs (barn, shed). Calculate area (length × width) and local rainfall to estimate yield (e.g., 1 inch rain on 1,000 sq ft roof ≈ 600 gallons).

- Gutters and Screens: Install leaf guards, downspouts with mesh to block debris.

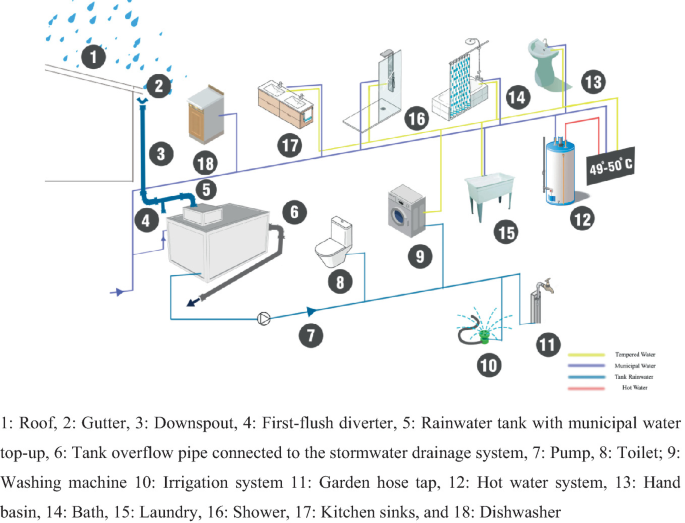

- First-Flush Diverter: Critical—diverts initial dirty runoff (e.g., 10–20 gallons per 1,000 sq ft roof). PVC or commercial units work well.

- Storage: Food-grade tanks/cisterns (IBC totes, poly tanks). Size based on needs (e.g., 5,000–10,000 gallons for small herd). Dark/opaque to prevent algae; elevate for gravity feed.

- Overflow and Siting: Direct overflow away from structures; place tanks 50+ ft from manure/latrines.

Filtration and Treatment Methods

- Pre-tank: Mesh/leaf filters.

- Post-collection: Sediment cartridge (5–20 micron), then activated carbon.

- Disinfection: UV for pathogens (especially poultry); simple sand/charcoal for low-budget.

- Blending: Mix rainwater with filtered well water to balance minerals/volume.

Species-Specific Guidelines

- Cattle (Beef/Dairy): 30–50+ gal/day (higher lactation/hot weather). Prioritize volume; soft rainwater boosts intake/milk.

- Goats/Sheep: 2–5 gal/day. Sensitive to copper/sulfates—rainwater often superior.

- Poultry: High bacteria sensitivity; UV-treated or well-filtered preferred.

- Pigs/Horses: 3–15 gal/day; good palatability key.

Step-by-Step Implementation Guide

- Assess needs: Calculate herd requirements (e.g., 10 cows × 40 gal = 400 gal/day) and rainfall data.

- Budget/ROI: Basic setup ($1,000–$5,000) pays back via savings (e.g., reduced pumping).

- Install: Gutters → first-flush → filters → tank → gravity/auto-fill troughs.

- Maintain: Clean gutters seasonally, flush system, test water.

Safety Testing and Monitoring

Regular testing is non-negotiable when relying on rainwater or filtered water sources for livestock. Even the best-designed systems can develop issues over time—contaminants can enter through poor maintenance, extreme weather events, or changes in local air/soil quality.

Recommended testing frequency and parameters:

- Annual baseline testing (or every 6 months in high-risk areas): pH, total dissolved solids (TDS), hardness, sulfates, nitrates/nitrites, iron, manganese, and total coliforms/E. coli.

- After major events: Heavy rainstorms, roof repairs, tank cleaning, or observed animal avoidance/behavior changes—test immediately for bacteria and turbidity.

- Monthly quick checks (small farms): Use portable TDS/pH meters and visual inspection of water clarity, odor, and trough slime/algae.

Acceptable ranges for most livestock (based on extension guidelines from NDSU, Penn State, and similar sources):

- pH: 6.5–8.5 (avoid extremes)

- TDS: <3,000 ppm (ideal <1,000 for dairy/high-producing animals)

- Sulfates: <250 ppm (calves/lambs), <500–1,000 ppm (adults)

- Nitrates: <10 ppm as NO₃-N (very strict for young stock)

- Total coliforms: <1,000 CFU/100 mL; E. coli ideally absent

- Turbidity: <5 NTU for clear appearance and palatability

Where to test: Send samples to certified agricultural/water testing labs (many university extensions offer affordable kits). In regions like Bangladesh, contact local Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE) offices, BRRI, or private labs in Barishal/Dhaka for livestock-specific panels.

What to do if results are poor:

- High bacteria → add UV or chlorination (low-dose shock, then flush).

- High sulfates/nitrates → blend with rainwater or install targeted filters (e.g., anion exchange for nitrates).

- Cloudy/taste issues → upgrade filtration stages.

Consistent monitoring catches problems early, preventing costly health issues and production losses.

Real-World Examples and Case Studies

Small homestead in a monsoon-heavy region (similar to Barishal Division): A goat farmer with 25 does and kids switched from a high-iron, moderately hard shallow tube-well to a 5,000-liter rainwater system fed from a 1,200 sq ft tin-roof shed. After installing a simple first-flush diverter, 20-micron sediment filter, and activated carbon post-filter, water TDS dropped from 1,800 ppm to ~120 ppm. Within two kidding seasons, copper-related issues (pale coats, poor growth) virtually disappeared, kidding percentages rose 18%, and the family eliminated monthly generator fuel costs for pumping. Maintenance: gutter cleaning twice yearly and filter changes every 9–12 months.

Mid-size dairy operation blending s ources: A 40-cow dairy in a semi-arid area faced chronic high sulfates (650–800 ppm) in the deep borewell, correlating with periodic polioencephalomalacia cases and 8–12% lower milk solids. They added a 20,000-gallon rainwater cistern supplemented by filtered well water (UV + sediment). Rainwater provided 60–70% of summer supply. Results: sulfate levels averaged 280 ppm in blended water, milk production stabilized, veterinary costs dropped ~35%, and the system paid for itself in under 3 years through reduced energy and health expenses.

ources: A 40-cow dairy in a semi-arid area faced chronic high sulfates (650–800 ppm) in the deep borewell, correlating with periodic polioencephalomalacia cases and 8–12% lower milk solids. They added a 20,000-gallon rainwater cistern supplemented by filtered well water (UV + sediment). Rainwater provided 60–70% of summer supply. Results: sulfate levels averaged 280 ppm in blended water, milk production stabilized, veterinary costs dropped ~35%, and the system paid for itself in under 3 years through reduced energy and health expenses.

Poultry layer farm success story: A 2,000-bird free-range layer unit previously used pond water (high seasonal bacteria). After switching to UV-filtered rainwater stored in black poly tanks, bacterial counts fell below detectable levels, egg shell quality improved (less bacterial penetration), and mortality from enteritis decreased by over 50%. Key lesson: UV was essential for poultry due to higher pathogen sensitivity.

These examples show that properly implemented systems deliver measurable ROI in health, productivity, and cost—often within 1–4 years depending on scale.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Even experienced farmers make errors that compromise rainwater or filtered water systems:

- Skipping the first-flush diverter — The first 0.1–0.2 inches of rain washes the dirtiest material off the roof. Without diversion, tanks quickly become contaminated.

- Using inappropriate roof materials — Asphalt shingles, treated wood, or old lead-painted surfaces leach toxins. Always choose uncoated metal or food-safe alternatives.

- Undersizing storage — A tank too small runs dry during dry spells, forcing reliance on poor backup sources.

- Allowing light exposure — Clear or translucent tanks promote algae blooms; use opaque/dark tanks or paint exteriors.

- Neglecting regular cleaning — Gutters, screens, and tanks should be cleaned at least annually (more in dusty/pollen-heavy areas).

- No blending strategy — In high-TDS well areas, using 100% rainwater can cause temporary mineral imbalances; gradual blending prevents abrupt changes.

- Ignoring species differences — Serving poultry the same minimally treated rainwater as cattle can lead to higher disease rates.

Avoiding these pitfalls dramatically increases system longevity and safety.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is untreated rainwater safe for livestock? No—raw roof runoff usually contains bacteria, bird droppings, and organic debris. Basic filtration (sediment + carbon) and preferably UV or first-flush diversion make it safe for most species. Poultry and young stock need the highest treatment level.

How much rainwater can I realistically collect from my barn roof? A simple formula: Roof area (sq ft) × annual rainfall (inches) × 0.623 = gallons per year. Example: 2,000 sq ft roof in a 90-inch rainfall area ≈ 112,000 gallons/year. After losses (first-flush, evaporation, overflow), expect 70–85% usable.

Can I use rainwater for dairy animals that will enter the human food chain? Yes, provided the system meets hygiene standards comparable to potable water (effective filtration + disinfection, regular testing). Many certified organic and grass-fed dairies successfully use managed rainwater.

What if my area has concerns about emerging contaminants like PFAS? Rainwater generally has much lower PFAS levels than groundwater in contaminated regions. If concerned, test specifically and consider activated carbon filters rated for PFAS removal.

How do I safely blend rainwater and filtered well water? Use automatic float valves or manual mixing in a common storage tank. Start with 30–50% rainwater and adjust based on test results to keep TDS/sulfates in safe ranges.

What’s the minimum investment for a basic system for 10–15 goats/sheep? Around BDT 40,000–80,000 (gutters, first-flush, 3,000–5,000 L tank, basic filters). Larger herds or cattle scale up accordingly.

Providing rainwater and filtered water for livestock is no longer just an eco-friendly experiment—it’s a practical, proven strategy that delivers healthier animals, lower operating costs, greater drought resilience, and often superior performance compared to relying solely on untreated groundwater or surface sources.

The key is intentional design: clean catchment, effective first-flush and filtration, adequate storage, regular maintenance, and diligent testing. Whether you’re a small homestead in Barishal raising goats for milk and meat, a mid-size dairy, or a larger commercial operation, starting small (even one tank for supplemental supply) allows you to experience the benefits with minimal risk.

Assess your current water quality, calculate your herd’s needs, check local rainfall patterns, and consult nearby agricultural extension officers or experienced farmers who’ve made the switch. With thoughtful implementation, you can turn rainfall—one of nature’s most abundant resources—into one of your farm’s greatest assets.