Imagine walking through your field or garden on a warm spring morning, only to notice fewer bees buzzing around your crops than in previous years. Your fruit trees are blooming beautifully, but the fruit set is disappointingly sparse. You’ve applied fertilizers, managed pests diligently, yet yields are declining. What if the solution isn’t more inputs, but rather embracing some of the very plants you’ve been pulling out as “weeds”?

Recognizing pollinator-friendly ‘weeds’ can transform this scenario. Many common plants dismissed as nuisances—such as dandelions, clover, and milkweed—are actually powerhouse allies for pollinators like bees, butterflies, and hoverflies. These beneficial plants provide essential nectar and pollen, supporting pollinator populations that in turn boost crop pollination and farm resilience.

As an agricultural expert with over 15 years advising farmers on sustainable practices, drawing from research by organizations like the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, I’ve seen firsthand how integrating these plants leads to healthier ecosystems and improved profitability. This comprehensive guide will equip you with the knowledge to identify, manage, and encourage pollinator-friendly plants in your fields and gardens, promoting biodiversity, reducing chemical dependency, Recognizing Pollinator-Friendly ‘Weeds’ and enhancing natural pollination services.

In the following sections, we’ll explore why these plants matter, debunk common myths, profile the top beneficial species, and provide practical strategies for integration—all backed by scientific evidence and real-world applications.

Why Pollinator-Friendly ‘Weeds’ Matter in Modern Agriculture and Gardening

Pollinators are the unsung heroes of agriculture. According to the USDA, animal pollinators—primarily bees—are responsible for pollinating approximately 35% of global food crops, including fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds. In the U.S. alone, pollinators contribute over $15 billion annually to crop production through improved yields and quality.

Yet, pollinator populations have declined dramatically in recent decades due to habitat loss, pesticide exposure, diseases, and climate change. The rusty patched bumblebee, for instance, has seen a 87% population drop since the late 1990s, per the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Monoculture farming and aggressive weed control exacerbate this by stripping away diverse forage sources.

The Critical Role of Pollinators in Food Production

Crops like almonds, apples, blueberries, pumpkins, and melons rely heavily on insect pollination. Without sufficient pollinators, farmers often resort to renting honeybee hives—a costly practice that topped $300 per colony in some regions in recent years. Supporting wild pollinators through habitat enhancement offers a more sustainable, cost-effective alternative.

Benefits of Tolerating Beneficial Plants

Allowing certain “weeds” to thrive provides multiple advantages:

- Enhanced Pollination: Diverse floral resources attract a wider variety of pollinators, leading to better cross-pollination and higher yields. Studies from the University of California show that farms with wildflower margins can see up to 20-30% increases in pollinator visits.

- Soil Health Improvements: Many beneficial plants, like clovers, are nitrogen-fixers, adding natural fertility to the soil and reducing fertilizer needs.

- Natural Pest Control: Increased biodiversity invites predatory insects that keep pests in check, decreasing reliance on insecticides.

- Erosion Control and Water Management: Deep-rooted species stabilize soil and improve water infiltration.

- Economic Savings: By fostering natural systems, farmers can lower input costs while maintaining or increasing productivity.

Research from the Xerces Society and Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) programs consistently demonstrates these benefits in regenerative farming systems.

Common Misconceptions About ‘Weeds’

The term “weed” is subjective—a plant in the wrong place. In conventional agriculture, we’ve been conditioned to view any unsolicited plant as a competitor that must be eradicated.

Not All Weeds Are Bad

Many so-called weeds are native or naturalized species that evolved alongside local pollinators. Invasive noxious weeds (e.g., kudzu or Canada thistle in certain regions) do warrant control, but beneficial volunteers like white clover or dandelions offer net positives when managed properly.

Why We’ve Been Trained to Eliminate Everything

The rise of broad-spectrum herbicides post-World War II, coupled with “clean farming” aesthetics, promoted bare soil ideals. Herbicide marketing reinforced this, but emerging evidence from regenerative agriculture shows diverse plant communities outperform monocultures in resilience and productivity.

Shifting to a Regenerative Mindset

Farmers adopting no-till, cover cropping, and pollinator habitats report not only healthier ecosystems but also reduced costs and improved crop quality. Organizations like the NRCS offer financial incentives through programs like the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) for establishing pollinator plantings.

Top Pollinator-Friendly ‘Weeds’ You Should Recognize and Keep

Here’s a detailed profile of 12 common beneficial plants often mistaken for weeds. These are widely distributed across temperate regions, though availability varies by USDA hardiness zone. Focus on observing pollinator activity and plant characteristics for accurate identification.

- White Clover (Trifolium repens) Low-growing perennial with trifoliate leaves and white/pinkish flower heads. Blooms spring through fall. Attracts honeybees, bumblebees, and butterflies. Excellent nitrogen-fixer; often used as living mulch in orchards. Control by mowing if it spreads excessively.

- Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) Rosette of jagged leaves with bright yellow composite flowers. Early spring bloomer—one of the first pollen sources for emerging bees. Deep taproot mines nutrients; edible for humans too. Mow before seed set to manage spread.

- Red Clover (Trifolium pratense) Taller than white clover, with pink-purple flower heads. Mid-season bloom. Preferred by bumblebees; strong nitrogen-fixer used in cover crops. Ideal for hay fields or rotations.

- Common Vetch (Vicia sativa) Vining legume with purple flowers. Attracts bees; fixes nitrogen. Good cover crop but can become weedy in some areas.

- Wild Mustard (Sinapis arvensis) Yellow cruciferous flowers. Early bloom supports bees; biofumigant properties suppress soil pathogens.

- Chickweed (Stellaria media) Low, sprawling with small white flowers. Year-round forage in mild climates; attracts hoverflies for pest control.

- Lamb’s Quarters (Chenopodium album) Nutritious “weed” with diamond-shaped leaves. Attracts beneficial insects; dynamic nutrient accumulator.

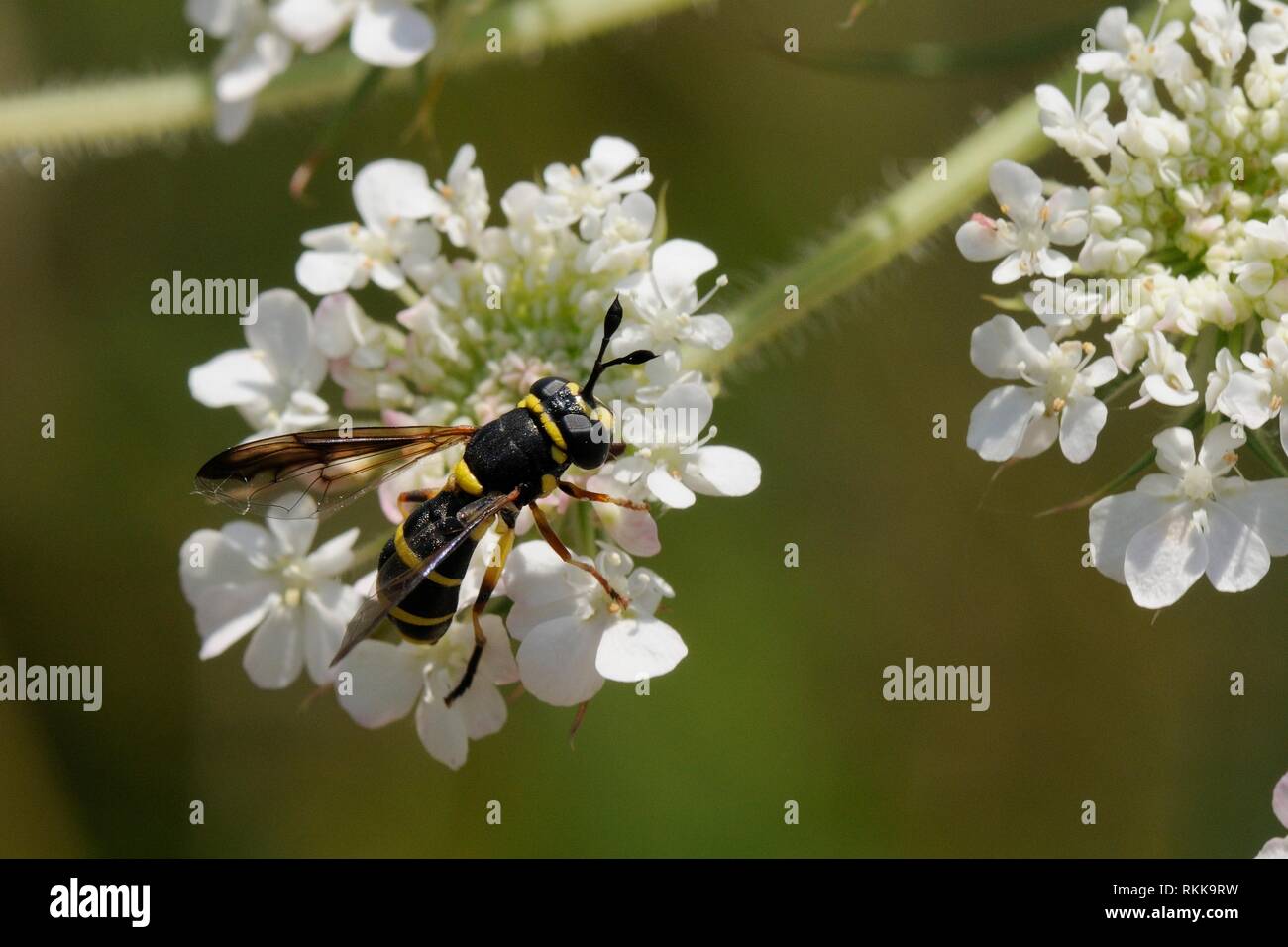

- Queen Anne’s Lace/Wild Carrot (Daucus carota) Umbrella-shaped white flowers. Draws hoverflies and parasitic wasps for natural pest control. Biennial; note central purple floret.

- Goldenrod (Solidago spp.) Late-season yellow plumes. Critical fall forage for bees preparing for winter. Often wrongly blamed for allergies (ragweed is the culprit).

- Joe-Pye Weed (Eutrochium spp.) Tall perennial with pink-purple clusters. Butterfly magnet; thrives in moist areas.

- Milkweed (Asclepias spp.) Essential host for monarch butterflies; milky sap and pod clusters. Nectar source for many pollinators. Plant native species to avoid invasives.

- Plantain (Plantago major/lanceolata) Broad or narrow leaves in rosettes; tall flower spikes. Attracts small bees; medicinal properties and soil compactor.

Tip: Use apps like iNaturalist or Seek for real-time identification. Always confirm with local extension resources for regional accuracy.

Comparison Table: Top Pollinator-Friendly Plants

| Plant | Bloom Period | Key Pollinators | Soil Benefits | Management Ease |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White Clover | Spring-Fall | Bees, Butterflies | Nitrogen fixation | High |

| Dandelion | Early Spring | Bees | Nutrient mining | Medium |

| Red Clover | Summer | Bumblebees | Nitrogen fixation | High |

| Queen Anne’s Lace | Summer | Hoverflies, Wasps | Pest control support | Medium |

| Goldenrod | Late Summer-Fall | Bees | Late-season forage | High |

| Milkweed | Summer | Butterflies, Bees | Monarch host | Medium |

How to Identify Pollinator-Friendly Plants in the Field

Accurate identification is the foundation of successful management. Many beneficial plants have look-alikes that are either less helpful or potentially problematic, so developing observational skills is essential.

Key Visual and Seasonal Cues

Pollinators prefer certain flower shapes and colors:

- Bees favor blue, purple, yellow, and white flowers with landing platforms (e.g., clover, mustard).

- Butterflies seek bright colors and clustered blooms (e.g., milkweed, Joe-Pye weed).

- Hoverflies and parasitic wasps are drawn to open, umbrella-shaped flowers (e.g., Queen Anne’s lace).

Bloom timing is equally important for providing continuous forage:

- Early spring: Dandelions, chickweed, wild mustard

- Mid-season: Clovers, vetches, Queen Anne’s lace

- Late season: Goldenrod, Joe-Pye weed

Observe the plant’s growth habit—low creepers like white clover versus tall perennials like goldenrod—to narrow possibilities.

Simple Field Tests and Observation Techniques

The most reliable test is direct observation:

- Spend 5–10 minutes quietly watching a patch during peak daylight hours.

- Note which insects visit: Honeybees, bumblebees, solitary bees, butterflies, and hoverflies indicate high value.

- Low or no pollinator activity may signal a less beneficial species.

Additional clues:

- Check leaf arrangement and shape (e.g., trifoliate leaves for clovers).

- Examine roots when possible—legumes often have nodules indicating nitrogen fixation.

- Smell crushed leaves: Dandelions have no strong scent; wild mustard has a pungent cruciferous odor.

Regional Variations

Beneficial species vary by climate and soil type. In the Midwest U.S., white and red clover dominate, while milkweed species differ between common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) in the East and showy milkweed (Asclepias speciosa) in the West. Always cross-reference with local resources:

- USDA PLANTS Database

- State agricultural extension services

- Regional Xerces Society guides

(Image: Close-up comparison of leaf shapes and flowers for accurate field identification of clover, dandelion, and plantain.)

Practical Management Strategies for Beneficial ‘Weeds’

The goal is coexistence, not dominance. Strategic tolerance allows these plants to support pollinators without compromising crop performance.

Selective Weeding Techniques

- Mow or trim before seed set to prevent excessive spread while allowing flowering (e.g., mow dandelions at 4–6 inches to permit bee access but limit seeding).

- Hand-pull only aggressive patches near high-value crops.

- Time weed control to protect bloom periods—delay spring herbicide applications until after early flowers fade.

Integrating into Crop Rotations and Cover Cropping

Many beneficial plants double as cover crops:

- Seed white or red clover into small grains or as understory in orchards.

- Crimson clover or hairy vetch in vegetable rotations fixes nitrogen and suppresses weeds.

- Allow volunteer dandelions and chickweed in fallow fields as early-season pollinator forage.

Creating Dedicated Pollinator Strips or Hedgerows

One of the highest-impact practices:

- Select field margins, fence lines, or low-productivity areas.

- Minimize tillage and sow native wildflower mixes supplemented by tolerant “weeds.”

- Aim for 1–5% of farm area in habitat—research shows even narrow 10-foot strips significantly boost pollinator diversity.

- NRCS and Farm Service Agency programs often cost-share seed and establishment.

Safe Coexistence with Crops

Monitor for competition:

- Keep dense patches away from crop rows during establishment.

- Use timed mowing to control height in pathways.

- In organic systems, these plants often outcompete truly problematic weeds by occupying niche space.

Expert Tip: Establish economic thresholds. For example, white clover is beneficial up to 30–40% ground cover in pastures; beyond that, renovate if needed.

(Image: Before-and-after view of a farm margin transformed into a pollinator hedgerow with native plants and tolerated beneficial species.)

Potential Risks and How to Mitigate Them

While most listed plants offer net benefits, context matters.

When a ‘Friendly’ Plant Becomes a Problem

- White clover can dominate pastures if livestock selectively graze grasses.

- Queen Anne’s lace is biennial and can form dense stands in neglected fields.

- In some states, certain milkweeds or vetches are regulated due to toxicity to livestock.

Mitigation: Monitor density annually and mechanically control excess.

Avoiding Toxic or Noxious Look-Alikes

- Poison hemlock (Conium maculatum) resembles Queen Anne’s lace but has purple-spotted stems and a foul odor when crushed.

- Common groundsel (Senecio vulgaris) mimics young dandelions but contains liver-toxic alkaloids.

Always confirm identification using multiple characteristics and reliable references.

Real-World Success Stories and Case Studies

Practical evidence reinforces these practices.

- A Michigan cherry orchard that established clover understory and wildflower borders reduced rented honeybee colony needs by 50% while maintaining yields (Michigan State University Extension case study).

- California almond growers participating in Project Apis m. seed pollinator strips reported 20–40% increases in native bee abundance and improved nut set.

- A Midwest row-crop farm using cover crop mixtures including red clover and volunteer mustard reduced synthetic nitrogen use by 30–50 lbs/acre while observing robust bumblebee populations (SARE-funded research).

These examples demonstrate measurable economic and ecological returns.

(Image: Thriving almond orchard with diverse understory supporting native pollinators.)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the easiest pollinator-friendly ‘weeds’ for beginners to recognize? A: Start with white clover (low-growing, three leaves, white flowers), dandelions (yellow flowers, jagged leaves), and plantain (rosette with ribbed leaves). These are widespread and unmistakable once learned.

Q: Will keeping these plants reduce my crop yields? A: When managed properly, no. Research consistently shows enhanced pollination and soil health outweigh minor competition, often resulting in equal or higher yields.

Q: How do I convince neighbors or landlords that these aren’t just weeds? A: Share USDA and extension resources on pollinator conservation, highlight cost-share programs, and invite them to observe increased bee activity during bloom.

Q: Are there pollinator-friendly plants safe around livestock? A: Yes—white and red clover are excellent forage. Avoid milkweed species toxic to some animals; consult local guidelines.

Q: Can I intentionally seed these plants? A: Absolutely. Many (clovers, vetches) are available as cover crop seed. For others, collect local seed or purchase native ecotypes.

Q: What if I farm in an arid region? A: Focus on drought-tolerant natives like showy milkweed or native goldenrod species suited to your zone.

Q: Do these plants help with organic certification or sustainability metrics? A: Yes—biodiversity enhancement supports many sustainability standards and can qualify for premium markets.

Q: When is the best time to start observing and managing? A: Early spring, as the first flowers emerge and pollinators become active.

Recognizing pollinator-friendly ‘weeds’ and integrating them thoughtfully represents a powerful shift toward resilient, regenerative agriculture. By identifying and supporting plants like clover, dandelions, milkweed, and goldenrod, you provide critical habitat for declining pollinator populations while improving soil health, reducing inputs, and potentially boosting yields through better natural pollination.

Start small: Leave a few patches untouched this season, observe pollinator activity, and document changes. The results—more buzzing bees, healthier soils, and sustainable productivity—will speak for themselves.

Your fields and gardens can become part of the solution to pollinator decline, one beneficial “weed” at a time.